- Home

- Gary Kemble

Strange Ink Page 8

Strange Ink Read online

Page 8

For Harry, it was pure hell. Because he couldn’t help but imagine Bec walking down that aisle. He would have gladly married her, even though things were less than perfect. Even though to some extent he’d had to mould himself to her idea of who he should be. Was that necessarily a bad thing? Already, he’d noticed his drinking had picked up, back almost to the point it was before they met. He was finding it harder to control his temper. And while he hadn’t actually lashed out at Simmo earlier that day, when he thought about hurting him it was as though someone else was in his head.

Simmo nudged him. Harry was still staring at the bright rectangle of light, even though Ellie wasn’t there anymore. She and Dave were holding hands now, as the celebrant took them through their vows. Everything was white. The walls, the flowers, Ellie’s dress. But in Harry’s mind, all was dark. He saw a face, eyes and teeth almost glowing in the gloom. Harry let his eyes go slack, knowing that if he tried to focus on the face, it would disappear.

His neck burned. The old man leant forward and dipped the bamboo shoot into a clay bowl filled with black. Then he sat up straight again and Harry saw the line of the woman’s shoulder. She had long, black hair. He couldn’t see her face, because the only light in the room was a candle, somewhere behind him. He felt her grip his hand, and he could smell her. Cheap deodorant. Sweat. The heady musk of sex. She drew in breath as the man applied himself to her neck. She leant back, almost in ecstasy, and he caught a glimpse of her face.

‘Harry!’ Simmo. Nudging him again. ‘Shit mate, you on the hammer? Is that part of your new biker look?’

Dave and Ellie were already on their way outside. There were tears aplenty in the crowd. The groomsmen were meant to form up with the bridesmaids, and Harry was standing there like a doped-up loser. His heart thudded heavily in his chest. He rubbed his face and moved forward, following Simmo’s lead. He offered his hand to his bridesmaid – he thought her name may have been Lisa, or Leela – and they walked out into the early afternoon. There were guests waiting to throw confetti.

Shit, people still do this?

Well-wishers milled around outside. Cars slowed as they passed, some to check out the wedding, others just worried about hitting one of the kids running around on the crowded footpath. A few clouds gathered in the west, but Harry doubted there would be a storm. But something big was brewing.

He walked around the side of the chapel, to where Simmo had stationed an esky for people to grab a quick drink before heading to the reception, which was going to be at a conference centre down by the river. There were soft drinks and poppers for the kids, and Harry had to admit that while Simmo could be a real dick, he wasn’t all bad. Harry reached in, pushing the imported beers aside until he fished out a VB.

Harry cracked the can, sculled deeply, then walked back up to the road. The photographer was busy with Dave and Ellie for the time being. Simmo and the other groomsmen were hanging with the bridesmaids. The best man had procured a bottle of champagne and was filling glasses, both for the bridesmaids and for his wife, who clearly wanted the bridesmaids to know that her hubby was off the market. They may have been fat and balding blowhards, but they were also accountants and engineers who’d been plying their trades for close to twenty years, while Harry was stuck on comparatively minimum wage. Money = power = sex appeal.

Out the front of the chapel was a zebra crossing, leading to a lookout that offered a great view of the city. There was a piece of quirky street art Harry had driven past countless times. It looked like a comfy lounge chair with a throw over the back. It was only when you got close you realised it was concrete, covered in small coloured tiles. It had already attracted a small gaggle of wedding guests, so Harry moved over to the stainless steel rail and looked out at the city.

He didn’t see it though. He saw the woman. The way her hair fell about her face. The line of her bare shoulder. The sharp intake of breath as the old man started tattooing her. And there wasn’t any doubt that that was what was happening. And he knew exactly what the tattoo was. A grid, filled with strange sigils.

She’s out there somewhere.

Harry felt his breath quickening, his heart racing again at the thought of meeting her.

‘Kyla.’

He spoke the name. He knew it came from the dreams. He didn’t know who she was, or why he was dreaming about her, or what the hell it had to do with people drowning. But he knew that he had to find her.

‘Hey.’

Harry turned. Dave was there. ‘Hey Dave.’

‘Photo time.’

Harry finished his beer. He went to move past his friend, but Dave grabbed his arms, gently but firmly.

‘You okay?’ Dave asked.

‘Lots of people have been asking me that lately.’

‘Well?’

Harry shrugged. ‘Not really.’

‘Is there anything I can do?’

Harry looked at the ground. Shook his head.

‘Harry, we’ll sort it out, okay? Just . . . just don’t do anything rash.’

It took Harry a while to realise what Dave was talking about. And then he flushed.

‘No. . . I wouldn’t. Thanks, man.’

Together, they walked back over the crossing, where people were still milling about in front of the chapel. Simmo filled them in on the deal with the photos. Dave and Ellie just wanted some basics with family and the bridal party. Then the newlyweds and the best man and maid-of-honour were heading to New Farm Park for some arty shots, before meeting everyone at the reception venue.

Someone had their iPhone out, watching news. Harry slowed. There was a white car, a government car, Australian flag flying from the bonnet. The guy holding the phone saw Harry looking over his shoulder.

‘It’s the PM. On his way to Government House. He’s gonna call the election. Mid-December, they reckon.’

Harry felt the sky darken, felt his limbs grow heavy. And he had no idea why.

CHAPTER 11

Harry chose the chair over the couch. Tom, the counsellor, said most people did on their first visit. The reality though was that he wanted to choose the couch, just to get some rest. There’d been no let-up in the nightmares over the past week. If anything, they’d intensified. With Dave on his honeymoon, he had no-one to talk to. And he felt as though it was all building up. Building up to what? He had no idea. He was exhausted.

The office was small. There was a bookcase on one side of the room, under the window, with various self-help books and also a stack of DVDs, again some self-help, but others you’d find in the ‘Drama’ section of the video shop. Trees thrashed around outside the window, and rain spattered against it. Another storm.

On Tom’s desk was an old computer monitor, with Post-it notes tacked to the side. Behind the monitor, on the wall, there were drawings by a small child. A photo in a frame leant next to his keyboard.

‘So, what’s up?’ Tom asked. He leant back in his chair, notebook on his lap.

Harry took a deep breath, and repeated the story. Starting with the break-up, moving into the new place. The first tattoo. The nightmares. His visit to the tattoo parlour. The second tattoo. More nightmares. With each telling, it became more like a story. Less real.

‘Uh-huh. And how long were you with your girlfriend – Bec?’

‘Yeah. Bec. Six years. We met at a party, mutual friends. You know the deal. I probably wouldn’t have asked her out except I was half cut. God, sometimes I wonder what she saw in me that night. And why she kept going out with me when she realised I was nothing like that person.’

‘I think even when we’re drunk some of the good stuff shines through.’

‘Maybe. Anyway, we hit it off. Had similar tastes in music, movies. Not perfectly aligned or anything, but. . .’

‘Some common ground.’

‘Yeah. She was living out at Menzies then, so it was kind of a long-distance relationship.’

He had fond and not-so-fond memories of those weekends there. An hour-and-a-half west of Br

isbane, at the foot of the range. When he could swing it, he’d take off early on Friday arvo to beat the traffic, then come home bleary-eyed but happy Monday morning, sometimes driving straight to work from her place.

‘She wanted to go overseas, do the London thing. To be honest, I’d never really thought about it. I didn’t have anything against it, just kind of thought it wasn’t my thing.

‘But, you know, when you’re with someone you see things in a new light. The thought of being there with her made it seem more manageable, more exciting.

‘We worked there for a couple of years – she managed to get sponsored so we were allowed to stay on longer than most people. We both worked casual so we could travel a bit. Did all the usual stuff. Paris, Amsterdam, Rome. A bit of Eastern Europe.’

Tom made a few notes.

‘How was travelling?’ he asked. ‘Some people say you never really know someone until you’ve travelled with them.’

‘It was great. I mean, it wasn’t perfect. We fought. There was one time, this disastrous camping holiday in France. I thought she was going to stab me with a butter knife. . .’

Cut or dig? Cut. Or dig?

‘Sorry, digressing a bit.’

Tom waved it away. ‘The digressions are often the good part.’

‘We came back and life just sort of carried on. I went back to the Chronicle. She got a PR job in the city. We moved in together. We didn’t even really discuss it. I mean, we’d been living together overseas. To me it meant: this is it, this is forever.’

‘But not for her?’

‘I broached the subject of tying the knot a couple of times. She always turned it into a joke or just changed the subject. I let it go. My parents separated when I was a kid. I don’t know, I think I wanted to prove that it could be done. That there was such a thing as a happy ending. But I figured if she didn’t want to marry, that was fine. Lots of couples don’t marry.

‘And then a couple of weeks ago I got home from work. She was sitting on the couch. She told me that she couldn’t imagine spending the rest of her life with me. We had a big talk. You could call it a fight, I guess. The mother of all fights.

‘I moved out. It was crazy. Wednesday morning I thought everything was okay. By Saturday I was moving my stuff into a new house.’

Tom made a few more notes, then put his book down.

‘Do you mind if I have a look at the tattoos?’

‘No, that’s fine.’

Harry swung around in his seat, put his chin against his chest. ‘This is the first one.’

‘Uh-huh.’

He felt Tom’s hand at the nape of his neck, fingers running over the ink, almost as though he were checking to see if it were real.

‘It looks Arabic,’ Tom said.

Then Harry pulled up his sleeve, showed him the drowning man.

‘Pretty full-on, hey?’ Harry said.

‘Mmm. I’ve seen more confronting tattoos. But yeah, it’s not exactly rainbows and unicorns.’

Tom made a few more notes. ‘Do you mind if I take photos?’

Harry shook his head. Tom opened the middle drawer of his desk, rummaged among old computer cables, notebooks and random pieces of paper, and pulled out a camera. He took a couple of photos of the arm, then the back of the neck.

‘Thanks.’

He placed the camera down on the desk.

‘So, am I crazy?’ Harry said.

‘We’re all a little bit crazy. Sorry, that must sound trite. The break-up has shaken you up a bit?’

Harry looked out the window, watched the raindrops flow down the glass. He could feel the tears coming, tried to hold them back.

‘Harry. If you need to cry, cry. Let it out.’

Harry thought he was going to, but then something clamped down. The tears dried up. The lump in his throat disappeared.

‘No, I’m okay.’

Tom shrugged. ‘You’re upset. Anyone would be, right? Anyone with feelings. It’s good that you’re upset.’

Harry nodded.

‘Harry, sometimes when people are under a lot of stress – and I mean a lot of stress – their mind kind of rebels. It shuts down to some extent.

‘It’s called a fugue state. Dissociative fugue. What happens is, on one level you keep operating, doing stuff. But when you become fully aware again, you can’t remember what you did.

‘The condition can be exacerbated by alcohol or other drugs. Like, maybe, having drinks at a buck’s night.’

Harry nodded.

‘You know Agatha Christie, the writer?’ Tom asked. ‘She once went missing for eleven days. Couldn’t remember a thing about what had happened. Must’ve been a hell of a hen’s night, right?

‘There have been cases where people have wandered off, caught a train to a new city, started new lives – only to regain their memories years later.

‘Sorry – not trying to freak you out. Most cases are short. Hours or days.’

Harry thought about just upping and leaving, starting afresh somewhere new. It almost appealed. But then a part of him, this new part of him, knew he had unfinished business here in Brisbane.

‘I feel like I’m splitting in two,’ Harry blurted. ‘I feel like there’s someone. . . I don’t know. I feel like I’m – losing myself.’

Tom nodded. ‘In a way, you are. You’ve just hit a major crossroads in your life. You have to find yourself again. Maybe the tattoos are part of that?’

He shrugged. He hadn’t really come to counselling for maybes. He was expecting more answers.

‘You said that a friend of yours told you the first tattoo was Persian? From Afghanistan?’

‘Yeah.’

‘And then the second tattoo. You said you got that one. . .’

‘It appeared. . .’

‘Yeah, you said it appeared after talking to Fred. So, in your mind you’d made the Afghanistan connection.’

Harry shook his head. ‘There were so many details in that nightmare, though. I mean, I’d heard about those asylum seekers, but I didn’t know the SAS were involved.’

‘You’d be surprised what your memory retains. Everything that happens to you – everything, right from birth – is stored in there somewhere. Even the stuff you can’t remember. Accessing it is the problem. Getting those tattoos. If we work on it, they’ll come back.’

Harry pictured the man, grinning in the darkness, all white teeth and bloodshot eyes.

‘I don’t know if I want the memories back,’ he said. ‘I’m just worried about what else I might do while I’m out of it.’

‘Understandably. There’s a range of things we can do to help. We can talk, like we have been. Do you know about cognitive therapy?’

‘I’ve heard of it.’

‘It’s basically rewiring your brain. Changing dys-functional brain patterns into more positive ones.

‘You can do creative therapy – using art and music to express your feelings. Hypnosis, so we can go deep and get to those memories.’

Harry felt a weird excitement at the thought of tapping into his memories. Part of him pushed away the idea, but a deeper part of him wanted to get it all out, like lancing a boil.

‘The other thing to remember is that, in many cases, people have one or two episodes and even without treatment, resume their normal lives,’ Tom said. ‘And maybe those memories never come back, but maybe that’s no biggie.’

Harry didn’t feel comfortable telling Tom, but he had a feeling this wouldn’t be the case with him. That unless he did something drastic, this was going to get worse and worse.

***

Harry sat at his desk staring at the screen while Christine tapped away productively next to him. Another edition had come out with a front-page story about a dangerous intersection. Harry had written the story, but he barely remembered it.

At the news conference with their editor, Christine did most of the talking, while Harry zoned out, drawing doodles on his notebook. Eyes, teeth, the line of a neck and long h

air, face in shadow, a drowning man, another one holding a tattoo machine, the line dripping and turning to blood.

Kyla. She was a part of the puzzle. But what puzzle? Did she have something to do with the tattoos? Was he under her spell? Was she somehow conjuring these fugue states? Screams. Terrified screams from a dark ocean.

Screams. But not that kind. He looked over at the TV. Andrew Cardinal was visiting a primary school on Brisbane’s southside. The kids crowded around him, waving pieces of paper for him to sign. Ron Vessel stood in the background, getting pushed further away as the mob grew.

‘What is it about kids and politicians?’ Harry muttered.

He remembered when he was a kid, the then-premier was mobbed by kids as he strode towards Parliament House on George Street. Harry remembered his dad gripping his shoulder, holding him back. Around home Harry had heard nothing but bad things about the premier, so he didn’t plan on running for an autograph anyway.

Harry was getting the same vibe from watching Andrew Cardinal on the TV. The newsreader was talking about new opinion-poll figures, showing that if the election were called today, Labor would win in a landslide. Out in the middle of the oval, Cardinal picked up a girl and lifted her onto his shoulder. For a moment Harry thought he was going to grab another kid to balance himself out. Some sort of impromptu circus act. But he didn’t. He just turned slowly, girl on his shoulder, grinning. Harry thought the act was a little odd. These days, adults had to be careful how they were around kids, and Harry suspected this was partly the reason why politicians always looked slightly uncomfortable, slightly stiff, during these kind of visits. But Cardinal didn’t care. Neither did Vessel, who stood there grinning, applauding.

‘It’s all over, bar the shouting,’ Christine said, ‘Right?’

Harry shrugged.

‘Come on! This guy’s a war hero.’

He was, except no-one knew much about his military service, other than where he’d served, because he was part of military intelligence. It was all secret. But the list of deployments was impressive enough: Kosovo, Rwanda, Iraq, East Timor, Afghanistan. Upon Cardinal’s retirement from the service, the chief of defence said that while much of what he’d done would remain classified for many years to come, there was no doubt that he had done a lot to make Australia a safer place. You couldn’t ask for a better endorsement than that. And he’d seen enough actual action – where bullets were flying and bombs exploding – to avoid the accusation that he’d merely flown a desk. Put him up against the PM and, yeah, he looked pretty good.

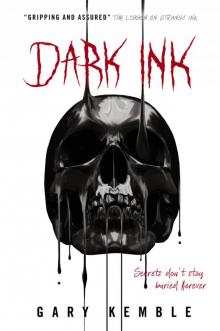

Dark Ink

Dark Ink Strange Ink

Strange Ink